Essentially, if you want to get from the south to the north of Europe here on its western edge, you have to go through Burgundy. The Gauls’ 5th century BC trade with ancient Greece moved along pretty much the same paths of least resistance that today are the autoroute and the high-speed TGV rail line.

So it is not surprising to find vines here. Everyone (especially the Romans) brought vines with them when they came. What is surprising, perhaps, is just how well the vine does here. Burgundy’s growing season is short and cool. So the grapes that the Romans brought with them would have been so far out of their natural habitat, it’s hard to imagine them ever ripening.

Finding the right grapes for this climate was obviously not easy. It took several centuries of monastic ora e labora and at least one royal edict to settle on the main varieties that we see in Burgundy today. And of them, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay stand out as the best-adapted to conditions here.

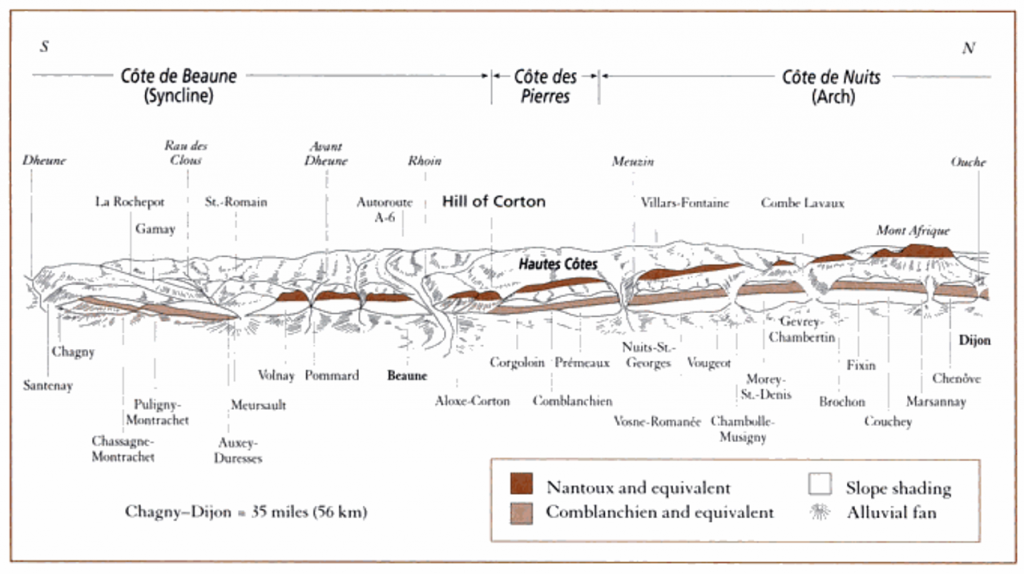

Once that issue was settled, the wines of Burgundy soon gained notoriety. And ironically, many of the places where the earliest settlements had sprung up, on the road to higher ground, turned out to be some of the best vineyards. Take a look at a map of the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune. But don’t look at the vineyards. Don’t even look at the villages. Look at the hills behind the village. And then look at that little valley where the road leaves the village, cutting up through the hillside. The French call that valley a combe, and almost every village has one.

Look again at the map, this time at the vineyards around the mouth of the combe. Imagine that there is a river of mud flowing at geological speed out of the combe and into the valley. What would happen? The mud flow would eddy around the mouth of the combe and deposit its silt on the crumbling hillside. And what vineyards lie in the zones around the edges of the combes’ eddys? Yep, it’s the grand cru and the premier cru.

This is a broad statement, but that is what we want to address here: the broad differences between the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune. So let me make another broad statement.

Imagine that you are standing in the plain to the east of the vineyards. You notice that the vines are planted mostly on the slopes. You see the combes. Look again at the map and you will see that the premier and grand cru vineyards, in addition to being bunched around the mouth of the combes, are mostly all at about the same altitude, the same distance up the slope.

Now step back even further into the plain until you can see the whole of the region. From where Gevrey-Chambertin is, on down to just south of Nuits St. Georges, you can say is a contiguous sheet of rock. This is the Cote de Nuits. And there, just south of Nuits St. Georges, that sheet of rock goes underground.

Then from there, from Ladoix on down to just south of Volnay, is yet another sheet of rock, broken by the combes and especially by that broader valley behind the Corton mountain. This is the heart, the northernmost part, of the Cote de Beaune.

Now get this: just south of Volnay, the sheet of rock that went underground up near Nuits St. Georges comes back to the surface. And though we still call this zone part of the Cote de Beaune, it has become something else altogether. This is where we the ‘golden triangle’ of white Burgundy begins. Meursault, Puligny-Montrachet and Chassagne-Montrachet, crazy as it may seem, all sit on the same slab of rock as the great reds of the Cote de Nuits.

But turn around again and look at the hillside. No combe, or none to speak of. What you see are the cliffs of Saint Romain, cliffs that never crumbled, and hence never silted out into the plain. Have a good close look at the map at the top of the page. It’s the essence of terroir and a graphic depiction of the famous ‘climats’ that make Burgundy wines what they are today.

Further Reading: Terroir, The Role of Geology, Climate and Culture in the Making of French Wines by James E. Wilson with a forward by Hugh Johnson.

Continue reading about the Regions.